Music is an important element of the Waldorf curriculum. According to Rudolf Steiner, the human being is a musical being, and the making of music is essential in experiencing what it is to be fully human. Music in the Waldorf curriculum awakens and nurtures the deep inner life of the child.

As the main lesson curriculum follows the very specific stages of child development, so also does the music curriculum. Engaging the soul activities of thinking, feeling, and willing in the child, the study and experience of the various elements in music arouse and cultivate the very forces necessary to be able to meet the challenges of the world with enthusiasm and confidence.

The music program in each Waldorf school reflects the specific skills, talents, and interests of the class teachers and of the music faculty. The size and configuration of the school building, the number of students, and the funding available also play a role. In every school, however, is the realization that music is necessary and essential to the entire Waldorf school experience.

What follows is a general overview of the Waldorf music curriculum. It briefly describes the music activities in each grade in view of the understanding of child development that underlies Waldorf Education. What is done in each grade builds upon the work of the previous year, deepening and broadening the skills and experiences already acquired.

It is in the early grades that Waldorf music education can look most different from traditional music education. It is not obvious that the children are acquiring musical skills. They are not yet reading traditional notation or keeping time to a strong beat. In the teaching of music, as in all Waldorf pedagogy, there is an awareness of the importance of bringing the right thing at the right time.

The first grader, for example, is at a particular point in his evolution as a human being. What is brought to him as musical experience must be appropriate to his stage of development. The young child does not experience music as an adult does. He is still living musically in a world of sound, tone, and rhythm that is, as yet, unformed and undifferentiated. The teacher must bring something appropriate to the child and bring it with reverence, imagination, and enthusiasm. The aim is not simply to teach children to sing and to play music, but to awaken qualities of soul.

Grade One

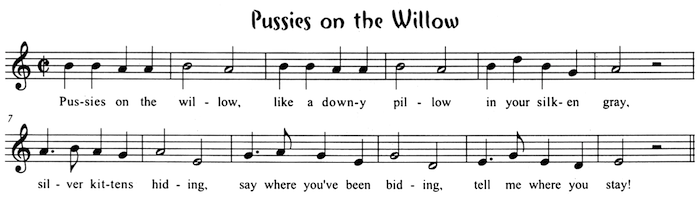

The six- or seven-year-old, still fresh from the spiritual world, is just beginning her evolution as a human being. She is “unfinished” and open to the outside environment. She experiences music as a surrounding, permeating force and feels that “the music sings me,” rather than “I sing the music.” Singing freely in the “mood of the fifth”—pentatonic melodies that employ open intervals of the fifth, moving around the central tone A—brings this floating, unfinished quality that is appropriate for the first grader.

A variety of instrumental sounds are used for “tone color” and mood only, not to accompany the singing with harmony or beat. The children sing songs about nature, the seasons, and the magical world of elves, gnomes, and fairies. Movement, dances, and song games address the in- and outbreathing qualities we strive to nurture both on the physical and the soul level.

In most schools, the first graders first learn to play a Choroi interval flute and then the pentatonic flute. These simple wooden flutes possess only the tones of the scale that create the larger, open intervals. Often the lyre is introduced in grade one. Improvisational games and activities are used extensively, and, above all, the experience of listening is cultivated.

Grade Two

Here, music continues to be presented so that it appeals to the feeling life of the child. Music in the “mood of the fifth” is gradually replaced by more purely pentatonic melodies. By the end of second grade, there are pentatonic songs that have a definite tonic ending—pentatonic major on G and pentatonic minor on E. The songs are about nature and the seasons, and also about the saints, heroes, and fable characters whom the children encounter in their main lesson blocks.

Work on the Choroi pentatonic flute and lyre is continued, as is the development of soul breathing. The second graders explore the polarities and contrasts in music, between listening and making music, high and low tones, loud and soft, fast and slow, and the exploration of various tone colors. This happens, still without the use of formal musical terms, still in the realm of feeling. Improvisation is continued. Some preparatory experiences are introduced as a prelude to composition and traditional notation, which begin formally in grade three.

Grade Three

During the third grade, most children go through the inner transformation that Rudolf Steiner called the “nine-year change.” The child incarnates more fully into the physical body, leaves the magical world of early childhood, and experiences himself as an independent being separate from the world. A number of new musical experiences are now appropriate: singing songs in a major diatonic key; playing the Choroi diatonic C-flute; and learning the rudiments of musical notation, though in an imaginative way. The keynote C is central now, providing a “landing,” or grounding point, for the child who is at this stage in the incarnating process.

Sacred songs and folk songs are important, as are songs about house building, cooking, gardening, and telling time—key subjects in the third-grade curriculum. As preparation for part-singing, the children learn songs in which they can experience call-and-response, drones, antiphony, ostinatos, and other steps toward singing in harmony. They make music lesson books that contain their growing musical vocabulary and that show their new skills in reading and writing traditional musical notation.

The musical element of rhythm tied to beat is introduced in the third grade. Steiner speaks of beat as “driving us into our bones,” so that it is now appropriate for the nine-year-old who is entering more deeply into the physical body and the material world. Simple percussion instruments are used to explore beat, rhythm, and other qualities of tempo.

For the younger child, performing for an audience engenders too much self-consciousness—literally. It is more appropriate to “share” the class workings at an assembly or other small classroom venue for parents with the children in their own circle, rather than facing an audience, whose gaze and focus is on them. After the nine-year change, the child’s awareness of her own individuality has developed sufficiently to meet this experience in a healthy way.

Grade Four

Having gone through the nine-year change, fourth graders are ready for another new set of musical experiences. If the proper preparation has been provided for part-singing and harmony, the children will now be able to sing simple rounds, canons, descants, and quodlibets (partner songs) with grace and ease. Holding on to one’s own part while listening to the other and to the whole is challenging, and the fourth grader is now ready to take on such an activity.

The curriculum includes the Norse myths, local geography, and local history. The children can learn their state song, local folk songs, and songs having to do with their regional geography. What they sing should express their growing strength and vitality and also their deepening inner life. Songs in minor and major keys are utilized, and the moods they engender are explored.

In most schools, children start to play a stringed instrument, usually the violin, in the fourth grade. If this has begun in grade three, then the fourth grade can be the time when some students opt for the cello or viola. Work on the C-flute is continued, incorporating harmony parts to accompany the singing, or part reading on the flute itself. Various keys and their accidentals are learned on the flute. In some schools, students work with instruments connected to the local culture: the ukulele in Hawaii, the hammered dulcimer in Appalachia, or the guitar in the West, for example.

The fourth graders continue their study of music notation, with the main lesson block on fractions nicely complementing the learning of the time signatures. Various meters are experienced and studied. By the end of the year, the children should be able to sight-read simple melodies, both vocally and instrumentally.

Since the children have “landed” in a world where music is a more external reality, deeper work with an instrument can begin. Private lessons, regular practice, and the striving for excellence, while hardening and stressful for the younger child, are now—well after the nine-year change—appropriate and manageable.

The child by the end of grade four has acquired important basic musical skills. The children of course come with differing musical aptitudes, so that their levels of skill will vary. And some children will have had the advantage of musical experiences and education outside of school. In a Waldorf school, however, the assumption is that every child has the innate capacity to sing and to make music and that this capacity should be developed as much as it can be.

The music curriculum in the upper grades of the Waldorf school brings the children ever more sophisticated and challenging musical experiences, but experiences that are appropriate to their stages of development.

Grade Five

In Waldorf circles, grade five—the fulcrum point of the grade school years—is usually referred to as “the Golden Age of Childhood.” The children realize or approximate a certain harmony and balance in their physical and emotional development. In addition to the study of ancient India, Persia, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, the study of the magnificent and inspirational culture of ancient Greece and the Greek ideal of grace, beauty, and balance is at the heart of the fifth-grade curriculum. The children strive toward this harmony, and their musical activities reflect and support this. Appropriate songs—such as “Glorious Apollo,” “Fair Moon,” and “Iona Gloria”—are songs that bespeak harmony and balance in form.

In Waldorf schools in the United States, American geography is also an important study block in the fifth grade. The rich American folk music tradition provides many songs and accompanying song games that are suitable for grade five. Examples of such song games are “Alabama Gal,” “Shoo Fly,” and “Godling, Godling.” These can be sung in two or three parts, so that the children develop skill in singing together in harmony. Many folk songs are either in the pentatonic scale or in one of the traditional modes. These tonalities are precursors to our more familiar major and minor scales and lend themselves well to improvisation.

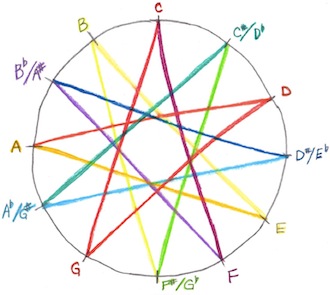

The children also study the basic principles of composition, learning how to create a score using the traditional notation that was introduced in grade three. Scales, as well as modes, are studied, and the musical key signatures are explored more deeply. This study includes the Circle of Fifths, one of the theoretical wonders in music and a foundation for the study of relationships in music scale tonalities.

The Circle of Fifths is a basis for the study of music theory in the later grades. Rudolf Steiner suggested that purely conceptual music theory is best brought at around age sixteen or seventeen.* Thus, for the fifth grader the Circle of Fifths should be presented in an imaginative and artistic way. The freehand geometry block in grade five provides an excellent opportunity for such a presentation. One can have the children create beautiful forms within the Circle of Fifths, indicating the relationships of the intervals and the key progressions.

The children may begin to study an orchestral instrument other than the violin or cello, such as the clarinet or flute. Or the string program can be expanded to include the bass viol. String ensembles of varied skill levels are formed.

In many schools, the children continue work on the diatonic Choroi flute, and, in others, the recorder is introduced. Some music teachers bring the alto recorder first, since its range is more like that of the fifth grader’s singing voice, and—because it is a new instrument with a new tuning and fingering— everyone can start afresh together, working from a common ground of experience. It is also possible to start with the soprano recorder only, or with both instruments.

Grade Six

In grade six, the children study ancient Rome. Therefore, this is the time for them to experience the Latin language through the many wonderful Latin songs and rounds available. During this study of Rome, songs that lend themselves to marching are particularly well suited to the sixth grader. Marching patterns and forms can be created together by the students and teacher and carried out with precision and intention while singing. Creating these exact forms echoes what the children are doing in the grade six geometry block, where they are studying classical Euclidean geometry and using compasses and protractors.

The Middle Ages is another focus of study in the sixth-grade main lesson. The music curriculum can draw on the vast and rich repertoire from medieval music history. The voices of most of the children are still pure and unchanged, and singing plainchant or Gregorian chant is a form and style perfectly suited for them at this time. “Pange Lingua,” “Ut Queant Laxis,” and the Kyrie from the “Missa Cunctipotens Genitor Deus” are wonderful examples of plainchant, a vocal musical form that expresses the important reverential aspect in medieval life.

If any children are experiencing the onset of the voice change of puberty, one can provide them with musical experiences in which they, too, feel successful and empowered. Girls’ voices begin to change at this time, as well, but their vocal shift is not nearly as dramatic as that of the boys. The changing male voice is often very limited in its range. Creating drones or ostinatos for a song is a way to give the boys something they can successfully sing, which not only contributes greatly to the musical experience itself, but also is in keeping with the style and quality of medieval music. Other aspects of music important during the Middle Ages are covered, such as the relationship of text to music, the spread of music around Europe, and the beginnings of notation and its development.

The sixth graders study acoustics as part of their physics block. This is a wonderful opportunity to integrate the music curriculum with the study of natural science by experimenting with and experiencing various aspects of sound and sound production. It could also be a time to explore creating new forms of notation for sound pieces composed in class. The students each bring in something that can make a sound, such as two rocks, pennies in a jar, waxed paper, or a lamp-shade, and the class creates a composition using these “soundmakers.” A form of notation is then created so that the composition can be expressed in written form and later replicated in performance. The symbols represent the duration, pitch (if applicable), dynamics, and any other musical nuances in the composition. This creative exploration can accompany the study of the development of traditional music notation from its origins in the Middle Ages.

The sixth grade is also an appropriate time to introduce the recorder, if it has not been introduced already in the fifth grade. The children can learn to play any of the four most commonly used recorders—soprano, alto, tenor—and, if their hands are large enough, the bass. The recorder appeared and came to prominence in the Middle Ages, and the medieval repertoire for the instrument is rich. There are many beautiful two-, three-, and four-part pieces that the class can now play.

In some schools, the recorder is presented in an earlier grade. But to introduce the instrument when the children are studying the historical period in which it gained popularity can be especially rewarding. The focused and overtone-rich tonal quality of a recorder is quite different from that of a Choroi flute and is more suited to the way the older child hears music and experiences tone. Thus the child’s aural development may be another reason to postpone the introduction of the recorders until sixth grade.

The recorder is a solo instrument and an instrument for consort playing, in which a small number of players play recorders of the various voices. A large group of children playing recorders at the same time can sound strident and unpleasant. For classroom playing, it is important to have good quality instruments in the various voices and, as much as possible, to keep all the recorders in tune with each other. Recorders are made of wood or of plastic. Plastic recorders are generally inexpensive, a good quality soprano costing perhaps twenty dollars. Wooden recorders range in price from inexpensive (twenty to thirty dollars) to very expensive. A high quality rosewood soprano can cost four or five hundred dollars. The standard of excellence in recorders is one made of wood, and anyone serious about playing the recorder as a solo or ensemble instrument would choose a high quality (and therefore relatively expensive) wooden instrument. There are, though, excellent wooden sopranos that cost less than fifty dollars.

An inexpensive wooden recorder, while made from a natural material and having a certain visual, aesthetic appeal and warmth, may not always be consistent in tone. Thus, some teachers prefer plastic recorders for the children. Although less aesthetically pleasing to some, a plastic recorder may be more consistent in tone than a comparably priced wooden one. To bring the highest quality musical experiences to the children, it is better to have instruments that create beautiful tone and have the ability to withstand the rigors of frequent classroom use than to use inferior ones for the sake of appearance. Excellent wooden and plastic recorders are now available, and care should be taken to choose the best instruments for a given situation.

Grade Seven

A focus of study in grade seven is the Renaissance— a period of cultural rebirth, world exploration, and discoveries in science, astronomy, and other areas. The students experience the rich vocal and instrumental repertoire of the age. Since the recorder was an important instrument during the Renaissance, the seventh graders continue to play music for that instrument, with all four standard versions of the instrument—soprano, alto, tenor, bass—now having been introduced.

Many of the children, both boys and girls, experience the changing voice during this year. While their vocal instrument is delicate and fragile at this time, it is very important that they continue singing through the change. Much can be lost if the voice goes unexercised. The music teacher honors the process of change, explains it, assists it, and supports it by providing music that the cambiata (changing voice) can successfully sing. Songs with a limited vocal range in the middle to lower parts serve this. As mentioned earlier, the use of ostinatos and drones can help these changing voices find their way in the choral setting and feel empowered in their contributions.

The study of physics in the seventh grade includes a block on the harmonic overtone series. This is an excellent complement to the deeper exploration of intervals and harmony in the music curriculum.

As the explorers of the Renaissance traveled the world, discovering things new and different, so, too, can the seventh grader experience other cultures through world music and the many wonderful folk songs from around the globe.

Grade Eight

The eighth grade is a year of challenges and changes. The students study the great revolutions— American, French, Russian, and Industrial—and the human striving after freedom and the realization of ideals. In their own development, the students are reaching the end of the seven-year cycle that began at age seven and are now entering adolescence.

The music during grade eight attempts to meet this turbulent, often disturbing, always inward, quality of the budding adolescent. It should reflect the profound changes that the student is going through in his experience of the world and of himself. Music with deep meaning and striving must be the basis of the musical experience during this special time. Ponderings about death, loss, and the struggle to know oneself can be brought in song to meet this inward process. “Ich Lebe Mein Leben,” “Immortal Bach,” and the “Winterreise” song cycle by Schubert all speak to these universal human questions.

Songs about the ideals of freedom, equality, and brotherhood are inspiring and uplifting to the eighth grader. Some excellent examples are “Hearken All,” “Freedom Is Coming,” and “The British Grenadier.” Songs that include riddles, puzzles, or humor are also welcome as they lighten the sometimes grave mood of the eighth grader. Continued work with the changing voice takes place, as does more theory (still presented in an imaginative way), composition, and increasingly complex part-singing.

Ensemble work is important in the eighth grade. Students of similar skill levels can form string quartets and other smaller groups, including vocal ensembles. In many schools, the students in the upper grades form an orchestra, which can undertake larger instrumental works. These various ensembles provide music for school festivals and special events throughout the year. They may also perform in the larger community, at a nursing home, for example, at community fairs, or at another school. Such performances give the students the experience of sharing their creative endeavors for the benefit of the larger whole. Sharing the gift of oneself in this way fosters a healthy sense of service to humanity. Also, ensemble work provides eighth graders practice in working with others to achieve a common goal.

Music in the Waldorf curriculum seeks to bring the living, healing presence of music into the life of the child and gives him an opportunity to experience both his own individuality and his relationship to community. It provides a chance for the expression of the soul, a discipline for achieving skills and goals, and contributes to the awareness of what it means to be truly human.

* Rudolf Steiner, The Child’s Changing Consciousness, (Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1996), 118–119. Lecture originally given in Dornach, April 1923.

© 2009 Andrea Lyman • This article first appeared in RENEWAL Magazine Volume 18, Number 1 – Spring/Summer 2009 and Volume 18, Number 2 – Fall/Winter 2009

Andrea Lyman holds a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in vocal music education, and taught music in the public school setting (K-12) for many years before becoming a parent and happily finding Waldorf education in 1992. She has been teaching Waldorf music since then, and received her certification in Waldorf Music Education in 2005 from Sunbridge College. She has taught music courses at Sunbridge College, West Coast Institute, and Sound Circle Center. She is currently president of AWME (The Association for Waldorf Music Education) and organizes its annual Waldorf Music Conference each summer, as well as traveling as a music mentor to Waldorf schools throughout North America.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.